Recalling J. Krishnamurti in the Times of Student Unrest

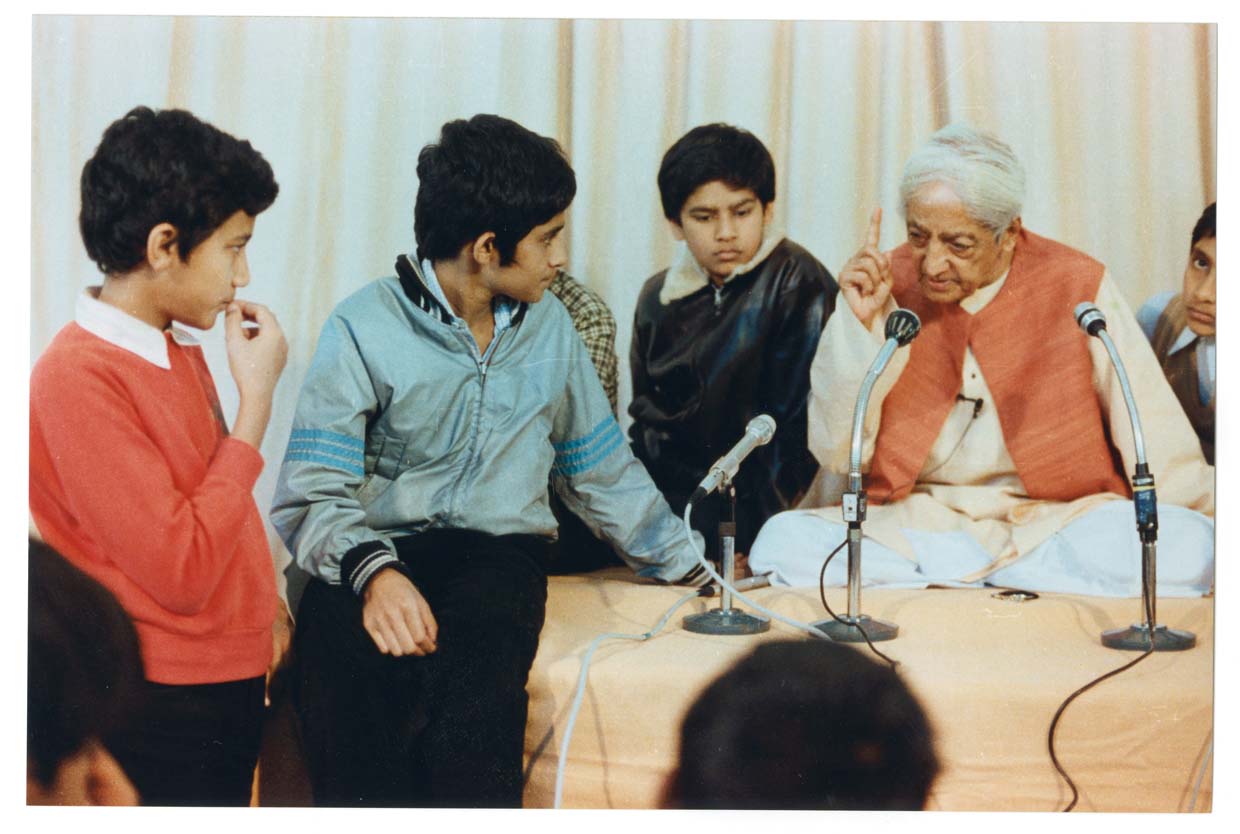

J. Krishnamurt was an Indian philosopher, thinker and speaker who made a valuable contribution to the fields of education, culture and religion. His ideas will continue to inspire and motivate us to rethink many aspects of our lives and to rebuild the lost harmony of existence. Here the author rediscovers his ideas in the context of recent student’s movements across the county.

Ananya Das did her Ph.D. from the Centre for the Study of Social Systems, JNU. She did her Ph. D from the Centre for the Study of Social Systems, JNU.

A zeitgeist of juggernauts and myths- this is how the 21st century would be addressed in the times to come. The myths themselves are a product of these juggernauts- of science and technology, of religions and religiosities, of ideals and ideologies. The claims of science over reason, of religions over imparting the true meaning to life, and of ideologies over progress form some of the greatest myths of our times. These myths scream for peace while propagating unfathomable violence in praxis. They create categories, images, and divisions conditioning our mind and knowledge along these lines. Science and its counterpart technology have produced too much of knowledge, religions have produced too much of explanations about the truth, and ideologies have created too many of social, economic, and political systems. Our existence and education are yoked in the yolk of these claims. Who needs a philosopher when we have scientists? Who needs a Krishnamurti in the times of Steve Jobs? Or when my religion is sufficient we do not need any other. This is the kind of absolutism and authority that these myths help build and propagate. The second aspect of these myths is branding. Hence it is always one form of knowledge preferred over the other, one form of understanding considered more sacrosanct than the other- a scientist over a religious minded person, a capitalist over a Fabian or university knowledge over traditional wisdom. This branding has a second aspect especially in the education sector- an IITian is inexplicably more intelligent than a student studying history, scientific exploration is considered greater knowledge than spiritual vividness.

This phenomenon does not stop here. The question of being is paramount in our education – I want to be a doctor or an engineer or a leader or a writer or an artist so on and so forth; my life would be comfortable and I can enjoy the pleasures of my hard work. These are extremely common refrains in explaining our lives. I want to know and I want to learn is poignantly conspicuous by their absence. The branding and the authoritarianism are so evident that we cannot even appreciate the beauty of a tree without being influenced by the prior knowledge and thoughts about it. Krishnamurti explains this:

You look at a tree, see it in the rain, see it in the evening and during the daytime, if you look at it with the memory you have about that tree, if you say that it is a mango tree or a tamarind tree or whatever it is, your botanical knowledge about the tree prevents you from looking at it.

It is in the backdrop of these observations that the recent student unrest needs to be analysed. This opportune moment brings to notice an important speech2 of Jiddu Krishnamurti explaining exactly this cringing sadness of students’ revolt witnessed in our country. Almost 50 years ago, on the then student unrest and campus violence in West Bengal and some other parts of the country, Krishnamurti had located its genesis in a greater malaise of the society. Student unrest cannot be grasped properly as a distinct act of violence. The phenomenon of violence has to be understood in terms of the total violence of man. The question he posed was: why does man live in violence. Why does he perpetuate violence?3 Intellectuals, scientists, philosophers and reformers have tried to give innumerable answers to this simple question. New systems, new philosophies, new leaders, new religions, new political parties, new knowledge systems have been created to put an end to this devastating and destructive relationship between humans. In spite of these tremendous efforts, the instinctive nature of acquisition and violence fails to be muted. According to Krishnamurti, “our mind- the human mind has been conditioned, shaped and moulded for millions of years to be violent, to create antagonisms, to be in conflict, to be at war”4. No novel systems of knowledge or economy or polity can possibly change the human mind. At the root of this violence is a conflicted human mind. We are at contradictions with ourselves. According to Krishnamurti, we keep our lives in departments- the business life, religious life, the social life, the family life, the national life, and so on- where there is such a division, which is a contradiction in ourselves, there must not only be violence but a dualistic existence5. The quagmire of a free market economy with its relentless pursuit of success and profit negates our potential to listen to the inner self, and this further aggravates this contradiction. Another important cause of violence is our constant effort to fit into a particular pattern established by society, religions and ideologies. We are disciplined to conform to a pattern. This truism was self-evident in the recent students’ violence in some of the universities and colleges. Left intellectuals-right intellectuals, comrades-sanghis, nationalists-seculariststhese conformities, these binaries, these antagonisms among fellow students, between teachers and students are desperate cries at the face of knowledge and development. Krishnamurti said, “Conflict arises only when there is accumulation of knowledge as opposed to learning- knowledge as the Hindu or the Muslim, the educated or the uneducated”6. Furthermore,as he said, “Knowledge is always in the past, knowledge implies the past”7. Scientific knowledge has been accumulating for thousands of years and action springs from that knowledge. But learning is constant movement without acquiring knowledge8. Thus, in spite of the denseness and far flung dimensions of knowledge- scientific, religious, ideological, secular, historical, and sociological- there is too little learning. Replacing systems, leaders, and

knowledge provides no solutions. According to Krishnamurti, What is necessary is a total mutation, a total transformation, of the whole structure and nature of the brain and of the mind also, because the crisis is so vast, so complex, not only in the technological world but also in the human world, in the world of daily living. It demands a new mind, a new heart, and this cannot possibly come about through any system. It comes only when human beings are inwardly aware of the fragmentations in the whole structure of their lives.9 Is it possible for us to not make science synonymous with reason; to not make religion the sacred path to deliverance; to not aim at only becoming; to not comprehend facts through ideologies; to not acquiesce only in categories? Can we stop being the angry Sisyphus10 and rock and roll our way through life? Will we learn instead of waiting for it to initiate learning? After all unlike Sisyphus we will not be here for eternity.

Notes

1. Krisnamurti’s speech on ‘The crisis in the technological and human world’ at a talk at The Benaras Hindu University, 1969, in Why are we being Educated, p. 9

2. Krisnamurti’s speech on ‘The crisis in the technological and human world’ at a talk at The Benaras Hindu University, 1969 3. Ibid., p. 1. 4. Krisnamurti’s speech on ‘The crisis in the technological and human world’ at a talk at The Benaras Hindu University, 1969, in Why are we being Educated.

p. 3. 5. Ibid.,

p. 4-5.

6. Ibid.,

p. 5.

7. Ibid., p. 14.

8. Krisnamurti’s speech on ‘The crisis in the technological and human world’ at a talk at The Benaras Hindu University, 1969, in Why are we being Educated. p. 15.

9. Ibid., p. 6-7.

10. Sisyphus is a legendary king condemned eternally to roll repeatedly roll a heavy rock up a hill only to have it roll down again as it nears the top.

This article is published in The New Leam, MARCH 2017 Issue( Vol .3 No.22 – 23) and available in print version. To buy contact us or write at thenewleam@gmail.com

The New Leam has no external source of funding. For retaining its uniqueness, its high quality, its distinctive philosophy we wish to reduce the degree of dependence on corporate funding. We believe that if individuals like you come forward and SUPPORT THIS ENDEAVOR can make the magazine self-reliant in a very innovative way.

Comments are closed.