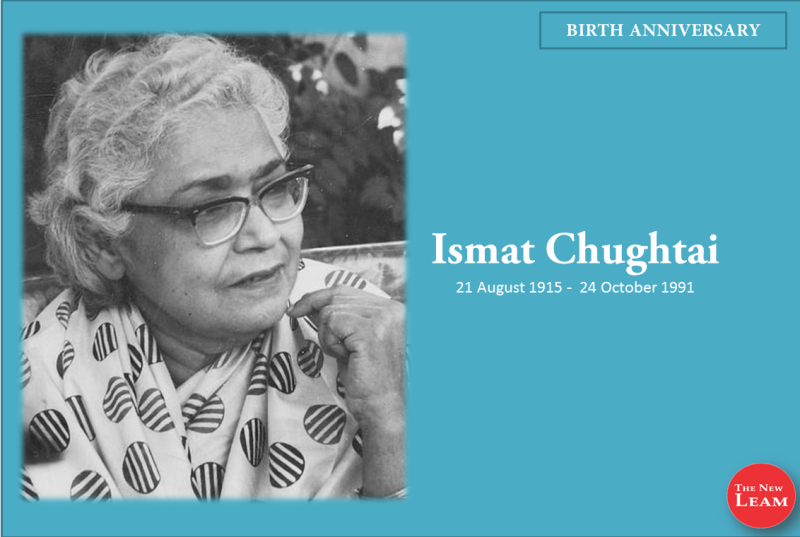

TRIBUTE

Any literary discussion based on feminist authorship in India cannot be complete without a reference to the works of Ismat Chugtai. Chugtai’s literary genius lay in her unapologetic addressing of issues often considered taboo and too bold for a woman of her generation.

The New Leam Staff

Today is Ismat Chugtai’s birthday. Ismat Chugtai was a contemporaray of other stalwarts like Saddat Hassan Manto and Rajinder Singh Bedi. As a female writer, she explored the considered as taboo areas of women’s sexuality, class conflict and morality in middles class homes. One of her most discussed short stories continue to be Lihaaf (The Quilt). The most celebrated Urdu author of her times, Chugtai was born in 1915, in Uttar Pradesh.

The stories of Chugtaai often explore themes such as homosexuality and its associated discomforts within the Indian traditional society. Chugtai’s bold and iconoclastic writing often received criticisms from readers and contemporary writers. Later, charges of obscenity were also levelled on her. She relentlessly wrote about women, their desires and the oppression they faced.

Her novel Tedhi Lakeer (The Crooked Line) continuous to be one of the famous works in Urdu literature. Ismat Chughtai passed away on Oct 24, 1991 and continues to remain an integral component of Urdu literature. Her writings continue to initiate discussions and debate among reader and literary critics. Here is a short excerpt from her autobiographical work ‘Kaghazi hai Pairahan’ translated from Urdu by Prof. M. Asaduddin.

I was a spoilt brat and used to get bashed up often for telling the truth. But when the disputes were taken to Abba Mian he would decide in my favour. My elder sister who had become a widow at nineteen was extremely bitter about life. She was greatly impressed with the high society at Aligarh, particularly the Khwaja family. I couldn’t get along with the begums of that family even for a moment. I was a madcap, outspoken and illmannered. Purdah had already been imposed on me, but my tongue was a naked sword. No one could restrain it. The world around me seemed like a delusion. The apparently shy and respectable girls in these families allowed themselves to be grabbed, hugged and kissed in bathrooms and in dark corners by young men who were related to their families. Such girls were considered modest. Which boy would have taken interest in a plain Jane like me? I had studied so much that when there was a debate I would beat to a pulp all the young men who were scared of the sight of books. They considered themselves superior to women merely because they were men! Then I read Angare on the sly. Rasheed Aapa was the only person who instilled into me a sense of confidence. I accepted her as my mentor. In the hypocritical, vicious atmosphere at Aligarh she was a much maligned lady. She appreciated my outspokenness and I quickly read all the books recommended by her. Then I started writing. My play Fasaadi was published in Saaqi. After that I wrote several stories. None of them was rejected. Suddenly some people began to object to them but the demand from magazines went on increasing. I didn’t care much for the objections. But when I wrote “Lihaaf”, there was a veritable explosion. I was torn to shreds in the literary arena. Some people also wielded their pens in my support. Since then I have been branded an obscene writer. No one bothered about the things I had written before or after “Lihaaf”. I was put down as a purveyor of sex. It is only in the last couple of years that the younger generation has recognized that I am a realist and not an obscene writer. I am fortunate that I have been appreciated in my lifetime. Manto was driven mad to the extent that he became a wreck.

The Progressives did not come to his rescue. In my case they didn’t write me off nor did they offer me great accolades. Manto became apauper in Pakistan. My circumstances were quite comfortable—the income from films was appreciable and I didn’t care much for a literary death or life. I continued to remain a follower of the Progressives and endeavoured to bring about the revolution!