Children throughout the country have been confined indoors and aren’t being able to attend school ever since the nationwide lockdown as a step to control and contain the spread of novel coronavirus was first announced, but children in the Jammu and Kashmir Valley haven’t had a regular school routine for much longer than children in other parts of the country.

As the Centre stripped the erstwhile state of Jammu and Kashmir of its special status and divided it into two union territories on August 5,2019, a complete lockdown and communication blackout had been imposed in the Valley.

This implied that the schools would remain shut for months and the government wouldn’t be certain when they would again be opened for the resumption of classes and the academic calendar.

When some schools did reopen after the government asked school managements to resume with the academic calendar, they saw scant attendance because parents were afraid of sending their children to school amid the communication blackout and the constant unrest that engulfed the political climate of the Valley.

Children of the Valley Denied Schooling Within a Hostile Political Climate

The historic decision on the scrapping of the special status enjoyed by the erstwhile state of Jammu and Kashmir and the its division into two union territories will forever be marked in the memories of the residents of the Valley, because it certainly changed their lives forever.

Within just a couple of months of the August lockdown, schools in the Valley announced a two and a half month long winter vacation from December 10 to February 2022. But again on March 11, the Jammu and Kashmir administration announced a closure of all educational institutions. The Valley then entered a second phase of lockdown but this time the reason was the coronavirus pandemic.

First a communications blackout and a total political lockdown and now a lockdown to control and contain the spread of coronavirus came to put a halt on schooling inside the Jammu and Kashmir Valley.

More than half a million children of the Valley have hardly gone to school on a regular basis since August 5, 2019.

Children throughout the country have been deprived of the concrete classroom space ever since the lockdown was first announced as a measure to contain and control the spread of the novel coronavirus.

But now schools have resumed their academic initiatives in the form of online classes and internet resources.

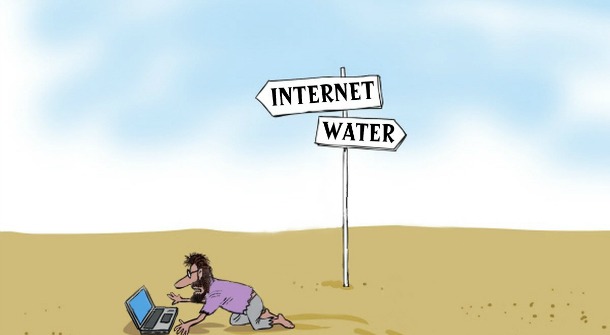

But this too is a difficult proposition in Kashmir because the ban on 4G internet imposed on August 5 and defined by the government as being necessary for security purposes is causing a lot of difficulties in accessing smooth running internet. There was a complete ban on mobile internet for nearly six months but later the government restored 2G internet for mobile phones and fixed internet services in the Valley. But it is important for us to acknowledge the fact that a minute section of the Valley’s residents use fixed line services and 2G internet connectivity is hardly enough to make the most of online learning.

Although many schools in the Valley like in other parts of the country did announce their plan for conducting classes online but in the absence of a fast internet connectivity, it looks like a difficult proposition to most children.

Most of the time, the connection gets lost and the sessions have to be stopped mid-way. Many of those working in the domain of education in the Kashmir Valley say that the lack of 4G internet connectivity in the Valley could seriously bring about a generation gap between students inside the Valley and those living outside it.

Although there are government issued guidelines for online teaching, children aren’t able to make the most of it due to the availability of 2G internet. All the interactive softwares and applications in the world today are 4G based, therefore a population that only has access to 3G is automatically left behind.

A group of media professionals along with many private schools in the Valley filed a plea in the Supreme Court which challenged the Internet curbs and said, “Our contention was to allow us to have online schooling so that we can close schools. Who knows how long this pandemic will continue? But they are making a mockery of things.”

But the Supreme Court heard the plea on May 11 and refused to pass an order to restore 4G internet and left the decision to the special committee led by the Union Home Secretary.

Disappointed Children, No Schools and No Internet Characterise the Valley

The school children in the Valley are extremely unhappy about being unable to access high speed internet and thereby being denied access to online learning resources like their fellow students in different parts of the country. What about the students and their future?

But despite the odds, schools n the Valley are making the best of the limited resources. In Kupwara district(northern Kashmir) teachers record and send video lectures through WhatsApp. On an average, recording a 15 minute lecture takes at least an hour.

Low internet speed means that online teaching has been reduced to teaching through sending online video and audio lectures through WhatsApp.

Teachers first shoot and record the lectures on their phones, upload them on WhatsApp and circulate it among students. Sending three to four videos per day seems a very challenging task due to poor internet connectivity but students and teachers are working towards making learning possible despite the odd. After the classes, teachers have to receive and examine assignments submitted by students on WhatsApp only. Sending a video lecture on 2G internet implies that the teacher has to constantly make sure that it is being uploaded.

Once the lecture is sent, it takes an equally long wait before the lecture is downloaded on the phone of the receiving student. Non-payment of or delayed payment of salaries in also a major worry for the teachers.

Surviving the lockdown with delayed payments is becoming a major cause of worry especially in the interior districts of the Valley.

Schools in Srinagar are doing a little better and many teachers are able to hold classes on applications like Zoom. But this does not mean that things are better there, because students are again faced with the problem of 2G internet connectivity on their phones. With schools planning to complete academic syllabuses through online teaching and even holding annual examinations online, children of the Valley may have greater difficulties as far their academic pursuits are concerned. Teachers in the Valley are also concerned about the questions around accessibility, lack of academic and curricular support structures at home which becomes extremely necessary at a point like this and of course the fact that even if the syllabus is completed its very difficult to ensure conceptual clarity and interest among students in the online mode of learning.

Moreover, online classes become monotonous and lack the vibrancy of the actual classroom. Being face to face with the teacher and with fellow classmates, children feel that the “real classroom”cant be replaced by a virtual classroom. There are concerns about children turning reclusive as they lose social contact and are being confined indoors due to the lockdown. Depression and anxiety are also threats to the child’s mental wellbeing.It is important for parents to ensure that they play an important role in making the lockdown an effectively creative, meaningful and engaged period for their children. The situation in the Valley is much more grave than anywhere else. The COVID-19 lockdown can be a new experience for those in the other states, but in Kashmir, political unrest and armed conflict have been going on for decades. According to a report by Doctors Without Borders, 45% of the Valley’s population suffers from some or the other mental distress. It is important to note that if such a large section of the population of the Valley suffers from mental distress, its children are certainly the most vulnerable. With financial insecurities and loss of livelihoods haunting parents, children are surely rendered much more vulnerable than we can imagine.

Zakir Afridi is a social activist based in Indore, Madhya Pradesh.